When people have talked about the “front line” of this pandemic, they’re often referencing the amazing doctors and nurses, fighting with every shred of their being to save their patients. However, in a world where there is no dividing line between us and the virus, where our community is interwoven with our enemy, we fight on many fronts.

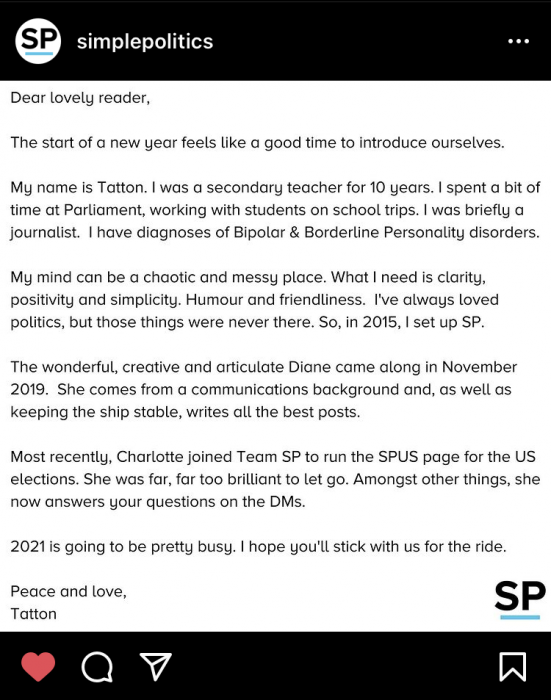

Nowhere is this more evident than with Tatton Spiller, the originator, voice, and mastermind of Simple Politics. There has been something comforting about the minimalist, clean messages of his you see shared across social media, which have become a familiar icon throughout the last ten months. He has worked tirelessly to tackle the virus with clear, precise messaging.

On Instagram, he has grown from “hovering around the 100,000 follower mark” a year ago, to now “chasing down 500,000”

“No-one is more amazed as me,” Spiller tells me over Zoom on a cold Monday morning, considering the meteoritic rise of his page to reach an audience of 700,000 across all platforms. “You know that growth – that’s 300,000 a year; we’ve put on 60,000 since New Year’s Eve”.

He is young, with a professional intensity. The office chair in which he sat down at six that morning twitches slightly as his eyes rake across the computer, waiting for the next story to break, even as he talks.

The secret behind the platform is the “clear, accurate, and impartial” simplicity of his message. He explains that “people are coming to us because they want to know what’s going on, and that is not always communicated very clearly by the media or the government”.

This is something that has been in desperate need since March – by May 2020, two months after the start of the pandemic, the danger caused by a lack of clear messaging was a well-recognised problem in Britain. An LSE study has shown that the range of messaging encountered by the public was “conflicted or inconclusive”, with a “lack of specificity” leading people to feel “in limbo”.

Spiller is surprisingly frank about this, telling me that: “Simple Politics shouldn’t exist. There should be no need for it, because there are media organisations that have loads of money and resources. And it doesn’t take much money and resources to run Simple Politics – it really doesn’t. So I don’t know why it exists. I feel a massive responsibility.”

With a spin-off podcast on its second series, a book, and a show explaining politics to children, the existence of Simple Politics is proved very much necessary.

I note a recent post detailing the predicted events of the next week which concludes with the admission that: “events will also, undoubtedly, take place that will rip this schedule to pieces”.

Asking him how he manages to manages to balance this obligation to keep his audience informed of a constantly changing situation, with any form of personal life, I received this startlingly honest reply:

“You’re not the first person to talk about this recently, and it’s difficult because the honest answer is I don’t cope. I just work all the time. Seven days a week. I was at my desk at six this morning – there will definitely be a briefing tonight, so it’ll be seven, eight, tonight I finish.

“You’ve got to be on the ball. Things can change. Things can change remarkably quickly. When I was typing that, it was the schedule for the week – it was like: “there’s nothing in this, like it’s scheduled to be ripped apart.” It’s scheduled with buffer space for things to come in. Things change. You have to roll with it.

“But I’ve got an audience of 700,000 across all platforms. I’ve got some lovely people donating money to keep it going. And I’ve got responsibility to them to cover it. It’s what I have to do.”

He started the page in 2016, having worked in Parliament’s education service, as a teacher and briefly as a journalist. He is open in his struggles with his mental health throughout this, suffering from bipolar, and borderline personality disorder – “I start doing well in a job, and then I have a little breakdown, then leave it and go and do something different”, he tells me.

Spiller seems to effortlessly amass the skills from this array of experience in Simple Politics: his knowledge of the inner workings of governance, the conciseness of a good journalist, and the clarity of an educator.

When he was an English teacher, Spiller explains: “You have to have the same level of enthusiasm with books you don’t like, as books you do like, because no one’s going to learn if you’re being grumpy at the front.

“So there’s a level of impartiality there, because the education you’re providing isn’t about you. That’s what I do with politics. I explain the way different people think, and I explain what’s going on, so that they can make up their own mind.”

The trigger for Simple Politics came when Spiller was working as a teacher, attempting to research and understand the first stages of the 2017 education bill, which changed the grading of exams from letters to numbers.

“I hit Google to try and find someone who was going to tell me what it was about, and no one did,” Spiller recalls. “I could find lots of political arguments, and people posturing, and saying this, and that, but I couldn’t find that right at the heart of it: what was going on.”

This frustration, and dissatisfaction with the lack of clarity in the subjects Spiller loves seems a clear theme as we continue to talk.

“I think a lot of political journalism is very self serving, and it’s very alienating to the audience. I’ve just received a text message from a senior minister. I don’t care. I want to know what’s actually happening. Not these rumours, not this unsubstantiated nonsense. There’s a lot of show-ey off-ey ness, and there’s a lot of not really trying to explain.

“A lot of the coverage says to people: “politics isn’t for you”, and that’s the opposite of what politics is about. If you go on the BBC news website, there’s a whole politics section, with the suggestion that there’s something else that’s not politics.”

“I’m going to look, right now, live with you,” he says, as I hear his fingers race across the keyboard. His eyes continue to dart through the page; he is clearly all too familiar with the site, and he finds an example quickly.

“Video of Indonesia, plane wreckage. That’s not a Politics story, but then we’ve got international travel, and plane safety, and all kinds of other political decisions that are behind it – that created it.”

This is something that has been particularly evident through Simple Politics’ treatment of the COVID pandemic. While remaining totally frank, they have cut through any media posturing to understand the facts behind the reports.

I mention one post in particular, which had garnered uncomplimentary comments, telling readers to be careful of the daily figures, and media headlines using them that are “designed to scare readers [and] should be taken with a pinch of salt”.

He explains his reasoning behind this to me in more detail:

“I get lost in data. That certainly wasn’t why I started Simple Politics: to stare at figures of the dead. It’s a miserable life. There are daily reported figures. And the reported daily figures are all the figures that the government has heard about that day, all the data that’s come in.

“So if the testing Centre in Manchester has some kind of IT issue, all the tests in that centre will build up and up and up and up, and then when they sought the IT issue, bosh, they all come out, and they all flood into the central computers.

“Over the weekend now 1,300 deaths were reported in a day. I have a lot of news apps, and every one of them sent me a notification to tell me about this high figure. Then yesterday, it was 60% of what it was the other day, and no notifications came through. Not one.

“So those figures fluctuate. At the moment, we’re trundling along at roughly 800 people a day dying. That’s huge. That’s horrible. 800 a day. But that’s nowhere near the 1,300 figure they’re quoting, and it’s much higher than the 500 figure that they don’t tell anyone about.”

This inevitably comes back to the true value, and purpose of Simple Politics. The way in which it is focused on informing its readers, rather than generating clicks.

“Sky are funded by advertising, which means they need eyes on the advertising, which means that they have to get eyes on that web page. The BBC needs to get viewers as well, because how can they justify spending licence fee payers’ money if they’re not getting a certain amount of people to look at them? Like I get, it, I just don’t think it’s great.”

This independence further aids Spiller, allowing Simple Politics to adapt quickly, and be constantly update its content offering.

“The great thing is it’s so lightweight,” he tells me. “We’ve got no management board to run ideas past. In 45 minutes we start the podcast again, because we can have an idea, and it can be online that day. We decided to start Simple Politics US, and we went from not having any idea we’re doing it, to recruiting, to starting in two weeks.

“It changes every day as we have different ideas. As we react to what’s going on.”

This is not something Spiller says to champion his individual skill – he is eager to admit his own faults, and give credit to those who help him run the page. In 2019, he was joined by Diane Daniels – “she’s been the perfect person to have alongside me, for the virus, the pandemic time, because she can be very focused and very serious in a way I’m not very good at doing.”

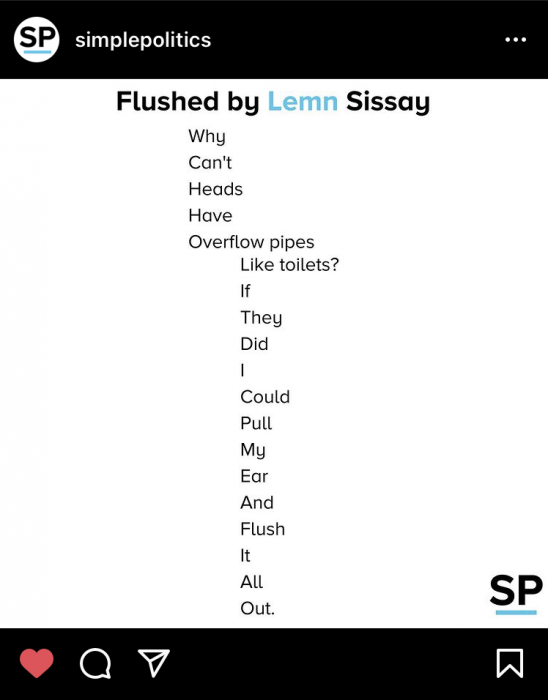

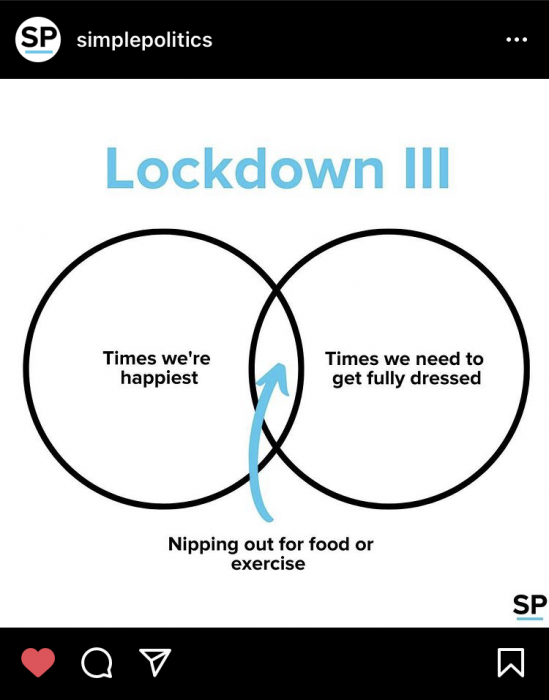

However, while the honest clarity of Simple Politics may bring readers to the page, they are kept there by the reassuring sense of community, with frequent light hearted, comical posts with reassuring poems, or lockdown memes even in the most dire of times.

There is a characteristic in the best journalists that seems to be an urgency to bring some sense of hope through the worst news. As I speak to him, I am reminded of Emily Maitlis speaking to Emma Freud, talking about covering the Grenfell fire with an uncharacteristic catch in her voice: “in the midst of all the horror and upset, I wanted to feel that I had ended that night by one piece of redeeming good news”.

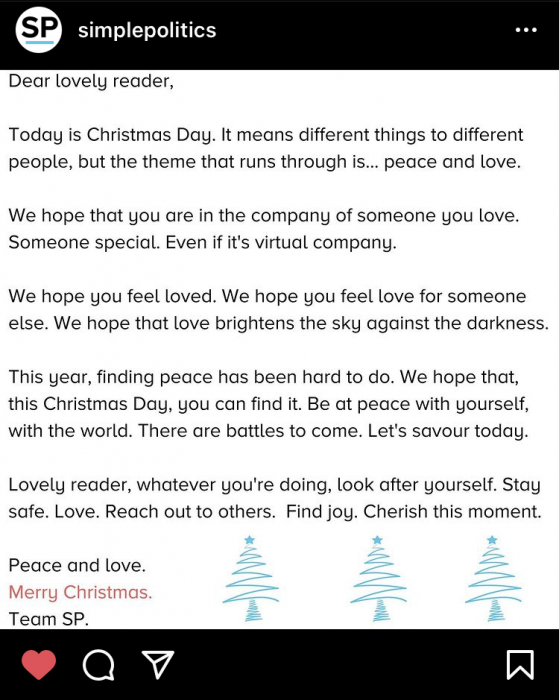

“There’s always a little bit of personality,” Spiller tells me. “A little bit of human interest, but actually it steps back when it needs to.” This is distinctly promoted through Simple Politics’ “Dear Lovely Reader” posts, which speak calmly and compassionately, directly to their audience.

“It’s always been important, because politics has been forged from years of Brexit division, and saying “let’s just not forget that the other side aren’t demons” seemed really important.

“And it’s from that spirit from which that develops. Now it’s just like, let’s talk about joy, and peace, and love, and not get bogged down because there’s so much sadness, and so much misery out there. That message I think is best to get across personally, just to talk openly, and honestly, and personally – it’s hugely important. “

To me, it is this spirit that puts Simple Politics ahead; the honesty and understanding of the posts have made them digestible, and avoided the overwhelming nature of all media since the beginning of the pandemic.

It places importance not only on the data it presents, but on: “peace, and love, and reaching out, and helping each other, and friendship, and support.”

These words seem to flow effortlessly from Spiller – it is clearly something he has thought about a lot. “Those things are so important in this time. [Mainstream media] are definitely not doing that, and I think that’s sad.”

Journalists covering horrific, traumatic events have often talked about being desensitised to the cruelty. I ask him if there is a detachment for him, rolling out these figures day in, day out.

“It’s the opposite. It pulls me in.

“I regularly watch the news and weep. Just the deaths, and people being ill, and people not having any money. And people being stuck in really small flats with children. And people not seeing their grandchildren, and being stuck in care homes, and just being scared and lonely. Teachers having to put perspex around the desk, and not talk to students properly. Supermarket workers who feel scared to go into work, and the abuse because people are stressed, and out of creme fraiche.”

Spiller’s service to his society through Simple Politics is clear through his efforts. He has fought the virus tirelessly, bringing so much comfort, so much clarity, to so many people.

Looking back through Simple Politics’ first posts, it is almost comical to see how their position, and the medium they cover has shifted.

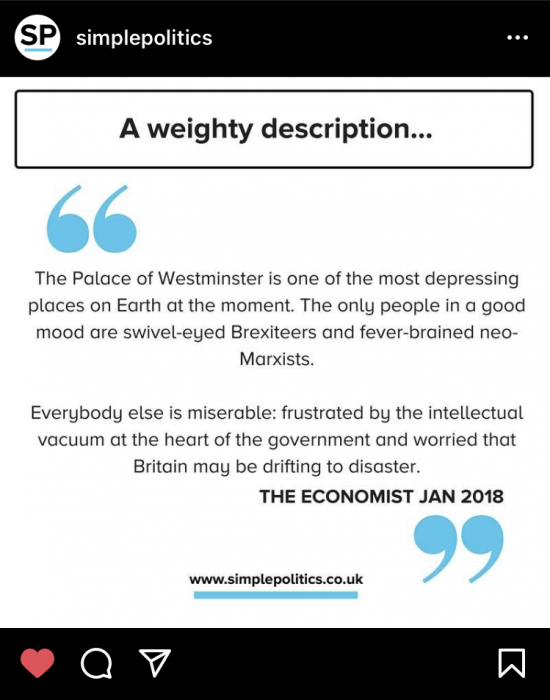

Searching back through echelons of his work two years before I interviewed Spiller, a post quotes the Economist, saying: “The Palace of Westminster is one of the most depressing places on Earth at the moment”.

It is not a quote that has aged well.

“Parliament, January 2018, was the thick of Theresa May’s Brexit. And it was the most depressing place in the world. It was just incredibly bleak. It was incredibly bleak. And there were these divisions, and the divisions represented the country, and MPs couldn’t agree. It was bleak and it was miserable.

“Just it’s not the most depressing place in the world now is it? There’s a lot of competition for that right now.

“I think this virus has changed a lot of things. I suspect that about two minutes past virus o’clock, people will go back to exactly the things they were. I hope that we can be less combative.

“I live in Whitstable in Kent, and for a long time, all of the virus was up where you are. And I, I’m not allowed to leave the house, because they can’t stop licking trees. You can see that frustration. Now it’s all in Kent, and you guys must be – ah bloody Kent! There are divisions.

“I think as a country, we’re not where we were in April, when we really worked together as a nation.”