In the ever-evolving world of dating, one shift is becoming increasingly hard to ignore: more and more Gen Z women are opting to date millennial men.

At first glance, it might seem like a harmless generational preference. But beneath the surface lies a much deeper story – one about politics, the internet, and a generation of young men lost to the red pill manosphere.

According to recent statistics, around 60% of Gen Z men are single, compared to only 30% of Gen Z women. This growing disparity suggests that many young women aren’t just opting out of relationships – they’re actively dating older. The reason? For many, millennial men seem more emotionally mature, politically grounded, and better equipped for adult relationships than their Gen Z counterparts.

This shift isn’t necessarily about women suddenly finding older men attractive. Women dating older men is nothing new, and historically, it has often been about access to resources, stability, and life experience. What’s new is why it’s happening now.

At the heart of this generational dating divide is a growing cultural force that has reshaped masculinity for millions of young men online: the red pill manosphere. What began as a niche corner of internet forums has exploded into a sprawling ideological web of YouTubers, TikTokers, podcasters, and influencers pushing a worldview where feminism is the enemy, women are inherently duplicitous, and masculinity is under siege.

The term “red pill” itself – borrowed from The Matrix – implies awakening to a supposed harsh truth: that gender equality is a lie and that traditional, patriarchal structures must be reinstated. But what’s marketed as male empowerment is, in practice, a breeding ground for resentment, authoritarianism, and deep misogyny. It trains boys to view women not as equals or partners, but as problems to be solved, manipulated, or punished.

Nowhere is this more visible than in the rise of Andrew Tate, a former kickboxer turned influencer who built a global empire preaching a toxic cocktail of ultra-capitalism, sexual dominance, and outright misogyny. Tate openly brags about manipulating and controlling women, has compared them to property, and frames male authority as natural and necessary. His reach among teenage boys is staggering. Despite facing legal battles and being banned from multiple platforms, his content continues to be reposted and repackaged by fans eager to emulate his worldview.

This red pill ideology doesn’t exist in a vacuum – it increasingly overlaps with far-right political movements that weaponise grievances around gender and identity to gain power. Many of these young men who begin by watching “how to talk to girls” videos or fitness influencers end up down pipelines leading to anti-feminism and white nationalism. It’s not a slippery slope – it’s a straight line.

What makes this particularly insidious is how it presents itself as common sense or even science-based. These influencers don’t always scream hate; often, they package misogyny as “truth,” as if biology or “human nature” justifies male supremacy. And because this content is so algorithmically optimised for engagement, young boys are often exposed to it before they’ve had the chance to develop critical thinking skills or alternative perspectives.

The results are showing up everywhere: in schools, where teachers report a resurgence of overt sexism; in politics, where the backlash against gender rights is intensifying; and now, in dating, where women are increasingly refusing to entertain relationships with men who see their autonomy as negotiable.

Millennial men – generally born between 1981 and 1996 – came of age before the full force of the red pill, incel, and “alpha male” movements took over corners of the internet. While not immune to misogyny or sexism, many of them missed the pipeline of influencers like Tate or YouTube personalities promoting a blend of hypermasculinity, conspiracy theories, and far-right politics.

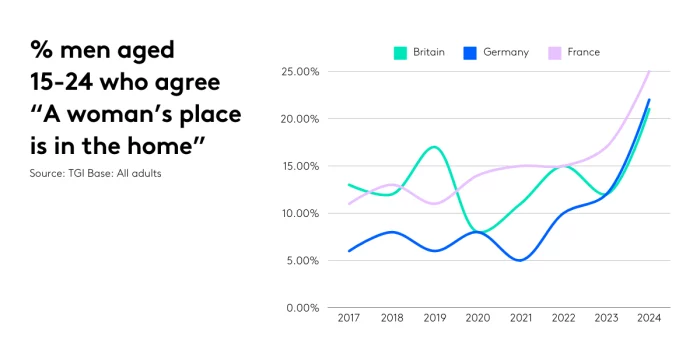

Gen Z men, on the other hand, have grown up with it. Social media algorithms have fed them a steady diet of content that teaches them women are evil and that being “too nice” makes them unattractive. The consequence? A generation of young men who, despite being more tech-savvy and culturally aware, often hold views on gender and politics that skew as conservative as the average 70-year-old.

Much of the current narrative around young men veering toward far-right ideologies suggests they’re doing so out of loneliness and social isolation. But that explanation has its limits. As many can point out, white, straight men have never truly been marginalised in Western society, and claiming they are now conveniently sidesteps a more uncomfortable truth: many young men are turning to these ideologies because they benefit from them.

Keeping the marginalised down – particularly women – uplifts the man. The only way these men interact with oppression is when they benefit from it, so it’s unsurprising that they turn to it now.

The male loneliness epidemic is undeniably a serious issue, but the way it’s being framed and exploited is not just unhelpful, it’s outright dangerous. Yes, many men today lack emotional support, but rather than confronting the root causes – patriarchal norms that discourage vulnerability, a culture that devalues emotional literacy, and the erosion of community – popular discourse has twisted male loneliness into a justification for misogyny. It’s no coincidence that these influencers have built empires by telling lonely young men that women are to blame for their isolation. The narrative has shifted from empathy to entitlement: men aren’t encouraged to build better relationships or interrogate why they feel alienated; instead, they’re told to reclaim control, dominance, and submission from the women who’ve “wronged” them.

What’s deeply cynical is how this loneliness is being commodified, not resolved. Entire online ecosystems now exist to radicalise vulnerable young men under the guise of offering them “support.” And yet, society continues to centre their pain, excusing or minimising the real harm these ideologies cause. Meanwhile, women are expected to be patient, understanding, and forgiving of men who see them not as equals, but as obstacles to be conquered. It’s not compassion, it’s a double standard that upholds misogyny and punishes women for men’s emotional failures.

While millennial men aren’t perfect, many of them learned how to form relationships and social skills before dating became an app-based game. They know how to talk to people, especially women, in person and were less exposed in their formative years to the dehumanising rhetoric now common in online spaces.

For Gen Z women, that’s a breath of fresh air.

This cultural shift is also being mirrored in popular media, particularly in television shows that explore Gen Z masculinity and its increasingly toxic entanglement with online ideology. Netflix’s Adolescence, for example, offers a strikingly honest portrayal of how young men are being shaped by the red pill internet. What makes Adolescence so impactful is its refusal to frame this transformation as inevitable or sympathetic – it’s not a story of “misunderstood boys,” but a sharp indictment of the cultural rot that’s having an effect on relationships and the treatment of women.

This very topic was brought up in conversation with a few close friends over a glass of wine, and our takeaway was unsurprising.

“Millennial men just feel less performative and less threatened by women who are smart, successful or political.”

“The media just says ‘yeah well they’re just young and easily influenced’, but women are also impressionable, and somehow we don’t all turn into fascists.”

What we’re seeing isn’t just about attraction, it’s about survival. Gen Z women are growing increasingly exhausted by the cultural work expected of them. Many are no longer willing to date someone who is still wrestling with whether women deserve equality.

This generational dating divide may seem anecdotal, but it reflects the broader shifts in our culture. The political radicalisation of young men, fueled by online influencers and amplified by social media, is not just impacting elections and discourse; it’s also reshaping personal relationships, intimacy, and trust.

In choosing millennial men, Gen Z women aren’t just opting for older partners, they’re choosing people who haven’t bought into a system that tells them women are the enemy. And for many, that’s no longer just a preference. It’s a necessity.