Grayson Perry: The Pre-Therapy Years exhibition, currently showing at York Art Gallery, is strikingly similar to a Rorschach test, used to establish the soundness of an individual’s psychological state. The ink-blot images printed on squares of card have been switched here for ceramic artefacts. When one steps into the confines of the gallery, confronted by pots printed with penises, plates embossed with anti-capitalist slogans, and platters portraying Perry’s own perception of idealised bodies, it’s important to remember that interpretation is subjective. Whilst Perry offers one perspective, it is for the audience to interpret each piece however they see fit.

Grayson Perry captures the zeitgeist of his era in much the same way as the punk poets that came before him, putting the whirlpool of modern society not into the form of spoken words, but instead into the medium of pottery. In clay, Perry gives us an image of his life and times as vivid as one would find in an Adam Curtis documentary, best seen in his new exhibition at the York Art Gallery: The Pre-Therapy Years. His art is unmistakably political and unforgivingly personal, touching on both explicit and identifiable moments from the artist’s life and on a broader social analysis.

Irony, satire, and flamboyancy are key proponents of Grayson Perry’s artwork, and, indeed, Perry himself. His first creation was conceived at the age of nine: an ashtray moulded and subsequently gifted to his mother.

Notably, Perry’s interests are varied and saturated in social and political commentary. Perry’s ceramics offer an insight into his insatiable fascination with Princess Diana, femininity and gender roles, pop culture, religion, mythology, and motorbikes.

Irony and contradiction are key themes throughout this exhibition. Indeed, Perry’s traditional pottery making methods, which originated long before the Neolithic period, are used in conjunction with modern photo transfer techniques to include contemporary pop culture motifs (see ‘Meaningless Symbols’, 1993).

Meaningless Symbols (1993)

A Design Which Implies Significance (1992)

Bottom platter: Claire as a Solider (1987)

Cracked and Warped (1985)

Artefact for the People (1990s)

Untitled (True Blue) (1980-1989)

The ceramic style of his work is deliberately wonky, making the pieces themselves both endearing and reflective of his eccentric personality. Using techniques like embossing, photographic transfers, and text, his works resemble a collage in both form and style. Some explicitly parody expectations of conformity, such as the thirty commemorative plates born of the same mould but with different images superimposed upon the same Essex landscape. Perry’s works also include symbols such as thrones, medieval-style crowns, three short films, and a wooden hutch designed in his teenage years for his pet cat.

One of the most noticeable leitmotifs of Perry’s work in this exhibition is order, and importantly, its arbitrary nature and its effects on the human psyche. This is equally true across the chosen themes of the work exhibited in this collection, whether that be the performance of gendered ideals, the restraints of a society left traumatised by Thatcherite fascism, or the path to escape through subversion. Perry invites us to examine the times of his life through a lens of kitsch, dry humour, and misshapen pottery.

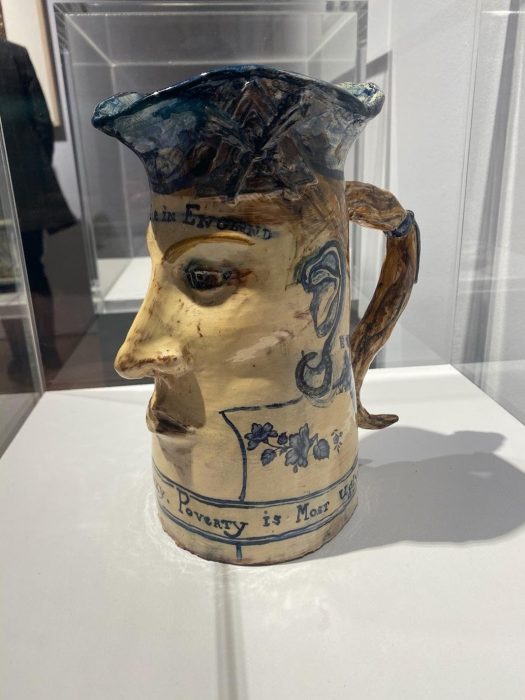

Perry’s sharp wit and dry sense of humour twinkles through the murky clay of ‘Saint Diana, Let Them Eat Shit,’ (1984), Perry’s most famous and widely known piece, and ‘Untitled (True Blue)’ (1987), a Toby-jug inscribed with a Perry proverb: ‘Hurrah! I Say Money is Sexy. Poverty is Most Ugly!’ The phrase, ‘Made in England’ is emblazoned across the jug’s pasty forehead, mocking the pompousness of Britain’s class-based system.

Besides artistic dexterity, Perry’s strength lies in his ability to express controversial opinions unapologetically, as displayed in many of Perry’s provocative pieces. Politically engaged, he links the irony of traditionalism and national identity to the injustice and inequality which seeps through the skein of Britain. Thought-provoking and bitingly candid, it’s enough to make even the most open-minded squirm.

Perry focuses the spotlight on gender: famous for his cross-dressing, we see the forms of femininity that the artist encountered in his early career, and those that he attempts to model with his alter-ego, “Claire”.

The exhibition showcases a particularly autobiographical selection of ceramics dealing with the artist’s deeply personal relationship with femininity and gender performativity. The year after his birth in 1960, a national scandal had surrounded the outing of April Ashley (a model) as a transgender woman; inspired by her bravery in the face of an intolerant public, Perry celebrates her in a plate likening her to a great ship in uncertain waters, a distinctly retro silhouette of a woman’s head faintly imposed upon the mast (‘April Ashley in Full Sail’, 1984).

Another autobiographical piece is ‘Newsreader’ (1990), a depiction of a Platonic ideal of the female anchor – effeminate yet serious, with a blonde bob rigidly hair sprayed to the journalist’s head – which Perry notes as an example of womanhood in the public eye, from which he drew inspiration for Claire. ‘Cocktail Party’ (1989), elaborates on this idea of an ideal type of woman throughout history, featuring an array of women dressed in Antoinette clothing, rags, and 60s cocktail dresses.

Femininity, in the eyes of Perry, is something that has been manicured and crafted down to the smallest detail – unlike his pottery, the feminine ideal is shown to be immaculate and held to the highest standards. Perry’s ‘Saint Diana (Let Them Eat Shit)’ (1984) further illustrates this critique: a miniature throne and toilet made from materials dredged from the banks of the Thames ridicules the cult of Princess Diana as an unattainable ideal coveted by millions of Britons, the title itself drawing comparisons to the lavish lifestyles of the French nobility.

Perry is unafraid to explore the world of femininity and identity. An anarchist at heart (or at least in the eyes of conformists), Perry goes against the grain of life. Ultimately, though, his authenticity and boldness in embracing his identity lovingly and wholeheartedly has served him well, and contributed to the success of his career as one of Britain’s best loved artists. By the early 90s, Perry had broken through the glass ceiling, transitioning from the fringes to the epicentre of the art world. In 2003, Perry was awarded the Turner Prize.

The provocative potter’s bravery in talking openly about his crossdressing, which manifests in the form of ‘Claire’, has undoubtedly offered comfort and encouragement to those who previously felt ashamed of their own rejected identities. The exhibition offers an intimate insight into a vulnerability never exhibited by Perry before, as we witness Perry’s own exploration of femininity and identity.

Perry’s uncertainty and experimentation with femininity is, intentionally or not, an accurate representation of naïve schoolgirls clumsily muddling their way into womanhood, lipstick, tweezers, and wax strips in hand. I appreciate Perry’s documentation of this journey through his ceramics, and I predict many people, both young and old, will see themselves reflected in at least one of Perry’s pieces. Through his work, we witness curiosity, acceptance, maturity, and growth.

Reflected in Perry’s ceramic work is a society obsessed with order, but devoid of meaningful culture. In the wake of immense social transformation in the 1980s, The Pre-Therapy Years sees British society as a place where the disillusioned are brought to heel by a carrot-and-stick of insincere art and a Thatcherite government approximating fascism.

Perry, at least in the “pre-therapy” years of his life, was deeply punk in his realisation of an anaemic and oppressed society in a neoliberal Britain. An urn entitled ‘I am the Myth Maker’ (1989) shows this in its details – what appears to be a horizontal band along the shoulder is revealed upon closer inspection to be a tangle of barbed wire and thorns, accompanied by an indentation of pound symbols and fearsome beasts, all atop a narrow, wonky foot – the myth-maker in question is the corrupting nature of capital, the foundation of the modern canon of culture.

‘For a Crazy Champion’ (1984) drives home the idea of life in a society of competition and hopeless toil – it depicts a blackened boxer surrounded by swastikas, a lavish cross, and an epigraph of reluctant sacrifice: “For a crazy champion who for his nameless kingdom rose and faced across the amyl nitrite-sodden sheet a foe hairless and colour of moonlit shit.” Similarly, ‘Now in our Green and Pleasant Land (ye dear olde bugger)’ (1988) features a mythical beast (which is, ahem, “overwhelmingly masculine”), inspecting a woman’s severed head with vignettes of rural England in the distant background. The scene is squeezed into the dish’s centre by hundreds of maker’s marks – symbols of authority and authenticity, ranging again from swastikas to symbols of the Roman Empire: the metaphor may be heavy-handed, but Perry never claimed to be subtle.

Iconography, symbols, and text also feature heavily in many of his pieces. Yet, whilst these creative methods were adopted intentionally, some of Perry’s ceramics were crafted by forces beyond the artist himself.

Take ‘Cracked and Warped’ (1985), for example. An upside-down self-portrait featured on an oval platter gleaming with oranges and blues. This piece was intended to be a single, coherent platter. Yet, when the final mould was placed in the kiln, an unexpected crack appeared naturally throughout the firing process. Rather than discarding the broken platter, Perry found humour in the mishap, celebrating the piece by declaring that the cracked ceramic was a declaration from higher powers, and that it was as though “God had passed judgement” on his work.

Grayson Perry’s greatest accomplishment – both then and now – was to hone in on the feeling of dissociation exclusive to our culture, and point to a path out of the madness: by understanding ourselves outside of the all-seeing eye of social expectation, he argues that we can hope to restore our senses of dignity in a satisfying and meaningful way. Self-fulfilment is a radical act, even if you stumble blindly onto it under the intoxication of several layers of irony. ‘Self-Portrait Cracked and Warped’ (1985) shows Perry in a sickly green hue, upside down below a caption of unimpressed commentary on his work: seeing oneself in the eyes of others isn’t healthy, nor is it natural compared to the transgressive and deliberate style that we find in Claire’s bright outfits.

‘Artefact for People who have no Identity’ (1994) compounds this critique, depicting a pair of people in the foreground of a run-down neighbourhood, one (with a 5 o’clock shadow) wearing a dress looking at the viewer, and the other glaring disapprovingly over his shoulder at the other. Mirroring American Gothic’s uncomfortable dynamic, this work situates a fear of the unknown in the recognisable destitution of a modern British scene. ‘Sales Pitch’ (1987) presents an equally galling (though comedic) side of this culture in a desperate appeal from the artist to a potential buyer, doubling down on the trope of the starving artist in a society that seemingly only cares about aesthetic – “but we’re different, aren’t we?”.

A self-induced vivisection has opened Perry up to criticism and mockery by critics and appalled onlookers alike. Yet, his penis-emblazoned pots and cutting exclamations inscribed in text across a sea of ceramics serve a purpose: to make the audience shuffle thoughtfully and uncomfortably. Some may search (or struggle) to find a deeper meaning, whilst others may question their own long-held beliefs. Either way, reactions will be provoked, for better or for worse.

And rightly so, for isn’t that what makes art…well, art?

The lost pots featured throughout Perry’s recent exhibition reveal a visual manifestation of angst, activism, cynicism, and absurdity. Perry dissents from the norms and expectations of stiff-upper-lip Britain and pokes fun at the hypocritical prudency of Brits. Kinky, political, and self-assured, Grayson Perry: The Pre-Therapy Years is not one to be missed.

Grayson Perry: The Pre-Therapy Years is currently exhibiting at York Art Gallery from 28th May – 5th September 2021. Get your tickets here: