Ten years ago, when ‘TikTok’ only brought to mind the hit Kesha song, a lot was different in the music scene. The charts were much more varied from week to week, and the biggest pop hits were accompanied by viral, instantly-recognisable music videos. But now, the charts seem less culturally significant than they once were, as well as the biggest music videos struggling to amass as many views as they once did. And TikTok is the culprit.

Of course, TikTok, alongside the rise of streaming platforms, have completely changed the way we consume music. Back in 2014, streaming was only just beginning to count towards UK chart positions, with CD sales still very high, at 55.7 million that year. But as streaming and Tiktok took hold, hearing the newest pop hits became much more accessible than before, only needing a quick few swipes for the algorithm to land you the newest trending songs. Unsurprisingly, CD sales last year were down at 10.5 million in the UK, and this dip in physical media sales has a massive impact on artists, who, unless they are in the Top 1%, struggle to make much revenue at all from Spotify or TikTok.

In terms of the UK charts, there’s a clear correlation between the rise of TikTok and streaming, and the decline in British artists reaching the Top 10. In 2014, 22 out of the 40 biggest songs of the year in the UK featured British artists, but last year it was just 9 out of 40, with Myles Smith’s ‘Stargazing’ leading in the 12th spot.

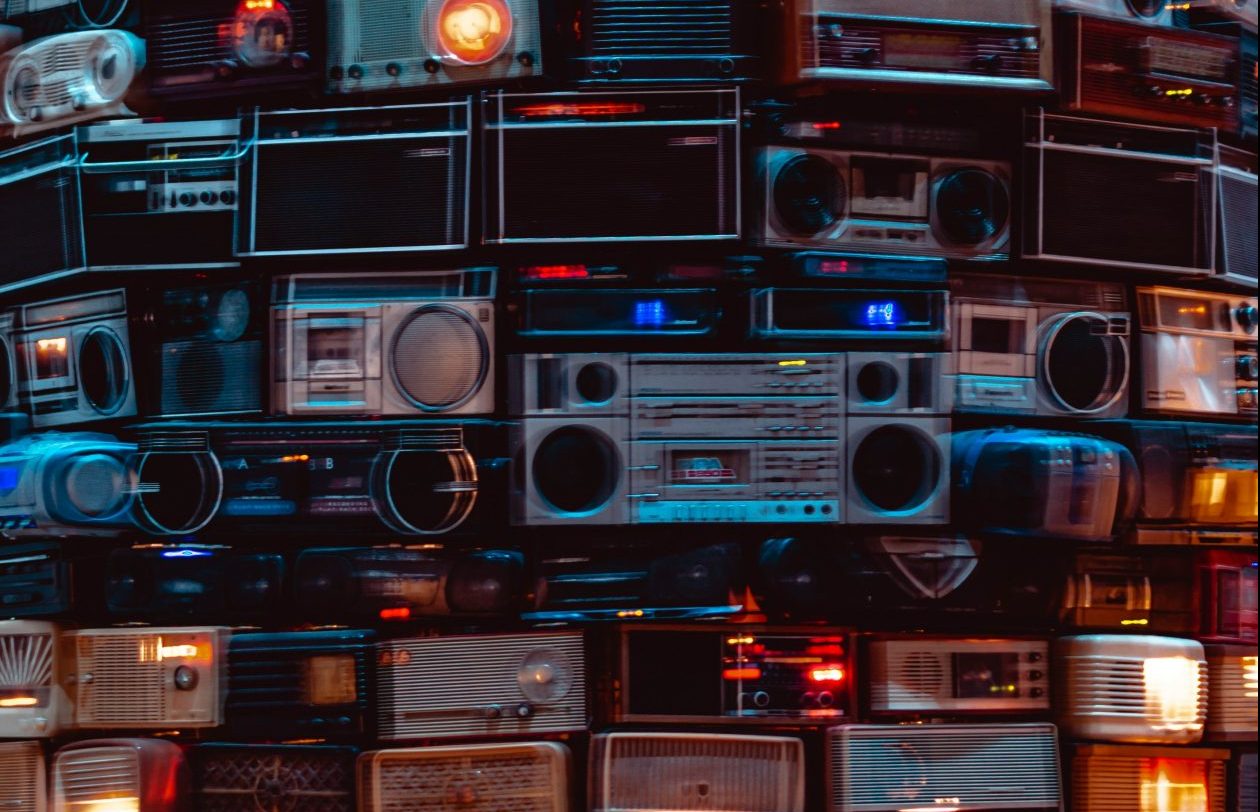

Radio used to have a big impact on what would become popular, with shows like Radio 1’s Drivetime attracting millions of loyal listeners, giving radio airplay a powerful influence over the charts. And further back in the golden days of BBC One’s ‘Top of the Pops’ during the 1970s and 80s, and Blur and Oasis’s 1995 Battle of Britpop, the charts felt like much more of a central part of British culture.

How we consume music has become much more fragmented, and the era of more singular, communal listening via radio and TV feels long gone.

But now, as streaming and TikTok are globalising the music scene, there is a much wider pool of viral songs from across the word, especially from the US, which largely overshadows the airplay British artists get on radio, as well as radio itself giving way to algorithm-developed playlists on Spotify and Apple Music. How we consume music has become much more fragmented, and the era of more singular, communal listening via radio and TV feels long gone.

A similar trend can be seen in the changing popularity of music videos over the last 10 years in the rollout of pop singles. In the 2010s, it was very difficult to think of the latest chart-topping hits without their music videos instantly coming to mind. Videos like ‘Wrecking Ball’, ‘Somebody That I Used to Know’ and ‘Shake It Off’ were massive points of popular conversation, leading to numerous parodies on YouTube (need I mention Bart Baker?) and were often just as recognisable as the songs themselves. They were also the easiest way to access the newest songs without paying, before free streaming platforms were as popular as they are now.

Yes, music videos today still have the potential to reach hundreds of millions of views, such as Sabrina Carpenter’s Espresso music video, currently at over 390 million views. But over the last few years, the biggest artists like Dua Lipa and Ariana Grande have struggled to get as many views as they once did. In the UK and North America at least, TikTok has overtaken YouTube as the primary platform to interact with short-form music content. Its viral, ever-evolving trends are perfect for getting songs out to much wider audiences. Taylor Swift’s Cruel Summer featured in over 2 million videos years after its initial release, and the viral dance to Charli XCX’s Apple massively boosted the album track’s popularity, notably, both songs don’t even have official videos. Music videos may now feel more laborious to actively seek out, rather than quickly consuming content from different people on your TikTok algorithm using the song. It seems music videos as a primary way of enjoying songs has faded in favour of a more personal, interactive relationship with new music on TikTok, via our favourite creators and unique algorithm.

Though I’m tempted to wallow in the nostalgia of music in a time before TikTok, when music videos were the main event and the charts much more animated, the app has had an undeniably positive impact on the ability for lesser-known artists to blow up without the need to get a record deal first. York’s own Beth McCarthy blew up on TikTok when a video she made featuring her song ‘She Gets The Flowers’ got millions of views and is now their biggest song on Spotify with 23 million streams. Getting discovered via the internet certainly isn’t a phenomenon just like the TikTok age – the likes of Lily Allen and Calvin Harris gained early traction on MySpace. But the sheer size and viewership on TikTok makes music of smaller artists discoverable on a much larger scale, in a more random way than being dictated by how much money a label pumps into a single’s promotion. The unpredictable nature of the algorithm makes gaining popularity closer to anyone’s game.

Supporting small artists monetarily and spiritually, by attending gigs is vital.

Still, engaging with local music offline is super important in a time where grassroots music venues are being closed more than ever, with 125 closures in the UK in 2023. Though TikTok can be great for artists and music in many ways, the roots of the craft remain in local venues. Supporting small artists monetarily and spiritually, by attending gigs at places like the Crescent and Fulford Arms in York, is vital to help artists make a living more concretely than relying on their TikTok Creator Fund or residuals from Spotify streams. I’m sure we’ll continue to enjoy engaging with music on TikTok until the next big platform arises, but what would make it even more enjoyable for the emerging artists on there, is showing our support in person as well as via our likes and reposts.