“It’s a film” my friend declares, “the one with Daniel Radcliffe” he adds for good measure. “Actually, I think you’ll find it’s a stage production, I saw it once in London” another voice pitches in. The truth of the matter is that The Woman in Black is in fact the title of novel by the distinguished author Susan Hill. Judging from a quick Google search, you wouldn’t think so. The search results prompt “film” or “theatre” but surprisingly not “novel” or even “Susan Hill”.

This draws my attention to the continuing trend (which seems to be becoming more popular by the minute) of stage and film directors looking to popular novels for the material of scripts. Only recently I went to York Theatre Royal to see Nicholas Wright’s adaptation of one of my favourite books: Pat Barker’s First World War classic Regeneration. I am always wary about such adaptations – both on the stage and on the big screen – because although many books have had their reputations bolstered by the success of their stage and cinema counterparts, many adaptations have fallen short of the mark. To return to The Woman in Black, popular opinion seems to confirm the view that, though the stage adaptation is work of merit which stands on its own, the 2012 James Watkins film attracts more divided criticism. When I think about it, The Woman in Black is a good example of the tricky relationship of book, play and film.

Last year I saw the Stephen Mallatratt adaptation of the novel at York Theatre Royal and was deeply impressed by the imagination of the production. I’m pleased to say that I went to the performance blissfully ignorant of the Daniel Radcliffe film but feeling slightly guilty about having not read the book. As far as reviewing the play was concerned, neither of these things proved a hindrance and I was able to enjoy an evening of terror without any preconceptions. However, I did leave the theatre feeling a slight injustice has been done to Susan Hill’s novel – though not by the stage adaptation. As the performance came to its grisly end and the curtain fell, members of the audience leapt up from their seats and declared “I really wanna see the film now”. The frequency with which I heard this exclamation was astounding. Was I the only person in the auditorium who felt compelled to search out the novel? Despite the fact that the programme had openly acknowledged its indebtedness to Susan Hill’s novel, the original article was forgotten in a moment. No need to doubt the power of film advertisement it seems.

In a society where just about everything can be accessed by the touch of a button, perhaps people have shied away from the novel in an act of lazy deference to the film – why spend days reading the book when you can get the gist in a few hours? I’m not sure that this is entirely the case but the film poster doesn’t help. Below the central figure of Daniel Radcliffe, at the bottom of the credits in tiny words is ‘Based on the novel by Susan Hill’. In other words: “if you’ve read the novel or seen the stage adaptation you’ll recognise the title: if not you’ll probably watch it because Harry Potter is slap-bang in the middle of the poster.” Whatever your reasons, it still seems a shame that the true ‘story-telling’ nature (‘story’ being the operative word) of Susan Hill’s The Woman in Black has been forgotten and left to the obscure credits at the bottom of the film poster.

This could well turn into a debate comparing Susan Hill’s novel with the Radcliffe film. But the book versus film is an age-old question and one which has raged fiercely over many online comment sections. So what about the question of book versus play? Or play versus film? Is there the same distinction? Shortly before I saw Pat Baker’s Regeneration realised on the stage, I put aside my fears that the novel which I cherished might be about to suffer a vulgar reinterpretation. I sidelined such worries by convincing myself that the stage adaptation could only serve to vividly enhance the novel without the risk of defiling the original prose: it was surely a win-win situation. If it was a success, the play could illuminate the novel through a previously untouched lens. If it was a failure – no matter – the pages of my prose copy lay safely untouched at home. As it happened, I did not go home dismayed. The stage version of Regeneration was entertaining and did not leave me feeling that I had been cheated: the adaptation was both faithful and expressive – accentuating the moments of drama with astonishing effect.

Perhaps that’s one of the main questions when appraising a stage adaptation. If the play fulfils the essence of the novel and leaves the audience with a sensation similar to the novel can it be deemed an unequivocal success? That’s not to say that there isn’t scope for re-interpretation or artistic licence. It’s a question of what the play is trying to be: an ‘adaptation’ using theatrical resources to represent the novel or, a play which bears the title but distorts the plot in a way that ultimately severs its ties with the novel. I’ve always thought that the BBC film of The History Boys by Alan Bennett is a great example of the former. It’s true that in this case the adaptation was from play to film but the principal is much the same. Thinking about this it becomes clear that the task of adapting a novel for the stage is no mean feat; the decisions of selection and abridgement could be ‘make or break’. Though there is much that endears the format of prose to the production of drama (the dialogue, division and subdivision into chapters and paragraphs) there are certain effects which can only be fully achieved in the original prose. This requires a certain sensitivity of approach which, judged correctly, can actively enhance parts of the prose by placing them in the sphere of drama where light, sound, proxemics, props, and set can emphasise and capture the latent drama.

Reading this back, I seem to have suggested that the transformation from novel to play or play to film is an ‘all or nothing’ process, and this is not necessarily the case. Recently, I sat down to watch the hefty 1984 film, Amadeus, which portrays the fictional murder of Mozart. The film is based on the play of the same name by Peter Shaffer who wrote the adapted screenplay. Both are, in their own way, masterpieces but in many respects they are quite different from one another – save for the actual plot. In light of this, it is interesting that the inspiration for the film and the film itself enjoyed such mutual acclaim. The play was lavished with awards and the film received no fewer than eight Oscars. This clearly shows that divergence is not unhealthy or even undesirable. Sometimes it comes back to the issue of the format. For example, one of the great achievements of the cinematic Amadeus is the depiction of Mozart’s operas complete with orchestra and audience – something which would be tricky to pull-off within the narrow confines of the stage. The play and film bear resemblance as much as the one format can resemble the other. Both commend strengths of their own, which is what makes the diversity so interesting.

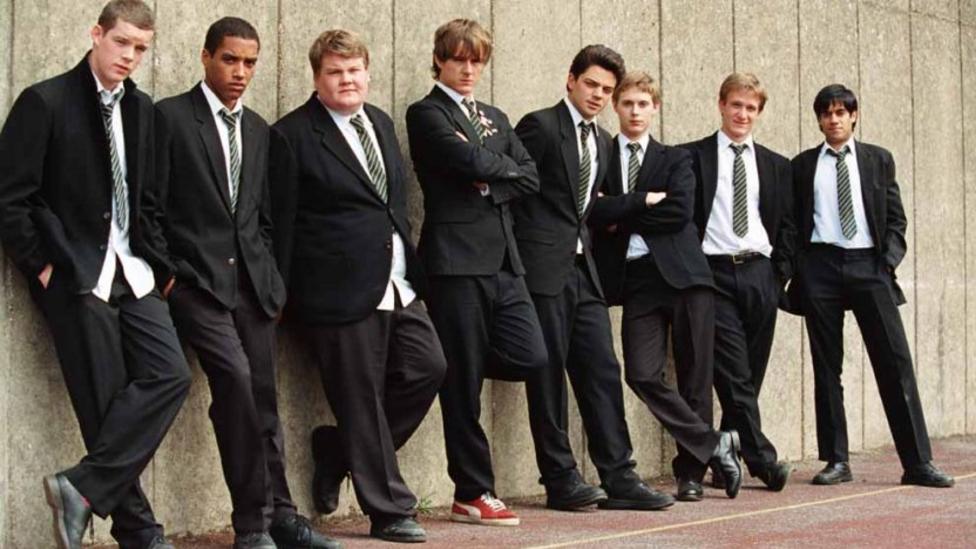

In light of the successes of recent stage adaptations – William Golding’s Lord of the Flies at the Drama Barn and Khaled Hosseini’s The Kite Runner at York Theatre Royal – we can be optimistic that there will be more exciting prose-drama transformations forthcoming. Certainly, with much of the current artistic attention focussed on the Centenary of the First World War, many more adaptations of classic war novels will soon be in the theatre. As the stage sensation of Michael Morpurgo’s War Horse continues to enjoy success around the world (receiving a notable reception in Berlin) other projects are garnering praise such as Hemingway’s A Farewell to Arms and Sebastian Faulks’ Birdsong.